Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

$ 14193 / $ 18000

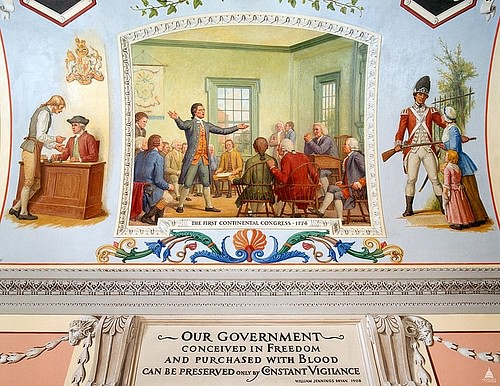

The was a meeting of delegates from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies of British North America that gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 5 September to 26 October 1774. Its primary purpose was to coordinate a response to the 'Intolerable Acts' recently passed by the British Parliament, although delegates also debated the rights of the American colonists.

By the time the Congress convened, the quarrel between Great Britain and its North American colonies was already a decade old. Time and again, Parliament had insisted on its authority to directly tax the Americans, who resisted, claiming that such attempts violated their constitutional rights to self-taxation and representative government. The lack of consensus between Parliament and the Americans regarding the colonies' place within the British Empire meant that neither side was willing to back down, leading to grandiose colonial protests such as the Boston Tea Party on 16 December 1773, when colonists dumped 342 crates of British East India Company tea into Boston Harbor. Hoping to make an example out of the impertinent Massachusetts Bay Colony, Parliament passed a series of punitive acts in 1774 called the Coercive Acts, better known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts.

AdvertisementDetermining that an attack on Massachusetts' rights was tantamount to an attack on American rights, twelve of the Thirteen Colonies sent delegates to Philadelphia to negotiate a boycott of British imports until the Intolerable Acts were repealed. Such an embargo on British trade, called the Continental Association, was passed, marking the most important achievement of the First Congress. The delegates also discussed the rights of Americans, a topic on which they were divided, and drafted a 'Petition to the King', in which they spelled out their grievances to King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820). The Congress was disbanded with the understanding that it would reconvene if the situation did not improve within the next year. However, before the Second Continental Congress could gather, the Battles of Lexington and Concord would be fought in Massachusetts, triggering the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

On the cold and gloomy evening of 16 December 1773, a crowd made its way along the rain-soaked waterfront of Boston, capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. It approached Griffin's Wharf, where three merchant vessels were tied up, each carrying crates of tea owned by the British East India Company, a corporate entity that had recently been granted a monopoly on the American tea trade by Parliament. Before long, a party of 30-130 men detached itself from the larger crowd and climbed aboard the three ships. These men, some of whom were dressed as Mohawk Native Americans, dragged the crates of tea on deck, smashed them open, and dumped their contents into the harbor, only to melt back into the crowd before they could be stopped. 342 crates of tea had been destroyed, amounting to £10,000 in damages (over $1.7 million in 2023 money). Having made their dissenting voices heard, the Americans now waited with bated breath for the Parliamentary response to make its way across the Atlantic.

AdvertisementWatching the punishment Parliament was inflicting on Boston, the other colonies realized if Massachusetts lost its liberties, they all would.

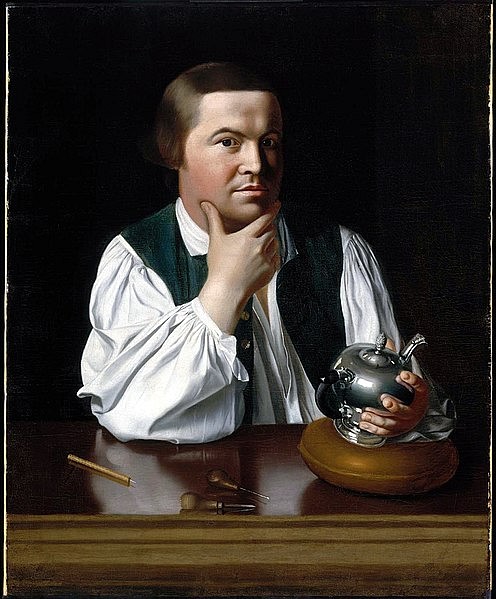

The Boston Tea Party, as the event was soon known, was the latest in a string of colonial protests that stretched back all the way to 1764, the year Parliament had passed the Sugar Act. The Sugar Act had not been anything too novel; indeed, a Parliament-mandated tax on molasses already existed, and the biggest change made by the act was a crackdown on smuggling. However, the passage of the Sugar Act loomed as a dark portent for colonists like Samuel Adams of Boston, who feared that a more substantial direct tax was coming. Indeed, Parliament imposed such a tax the next year in the form of the Stamp Act, which required colonists to pay a tax on all paper documents, including newspapers, legal contracts, liquor licenses, calendars, and more. For Adams, the colonists could not afford to pay such a tax without forfeiting their liberties; to do so would reduce them to the status of "tributary slaves" (Schiff, 73). The reasoning for this was the belief that, when the colonists' ancestors had crossed over to the New World, they had brought their constitutional 'rights as Englishmen' with them, including the right of self-taxation. Since the Americans had no representatives in Parliament, they contended that Parliament had no authority to tax them; the colonies' allegiance, after all, was to the king, not the people, of Great Britain.

Such was asserted by various colonial assemblies, including Virginia's House of Burgesses, the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and by the Stamp Act Congress, a gathering of delegates from nine of the colonies that met in New York City in 1765. These bodies all denounced the Stamp Act as a violation of Americans' rights, citing both the British constitution and their own colonial charters. These protests, alongside nonimportation agreements made by colonial merchants and violent riots in the streets of Boston, persuaded Parliament to rescind the Stamp Act in early 1766.

Advertisement

Many members of Parliament did not quite understand what all the fuss was about in America. They agreed that the colonists enjoyed the rights of Britons but claimed that the colonists were no different from the majority of Englishmen, who owned no property and could not vote but were still virtually represented in Parliament. To solidify its authority over the American colonies, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act of 1766, in which it asserted its right to issue legislation for the colonies in "all cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 133). This was closely followed by a series of additional taxes, called the Townshend Acts (1767-1768). The colonies once again erupted into protest over these acts, with heightened tensions culminating in the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770.

The Townshend Acts were repealed in 1770, but Parliament retained a tax on tea; along with the East India Company monopoly, this tea tax was what the colonists were protesting when they dumped the 342 crates into Boston Harbor in December 1773. Realizing that the colonies would have to be disciplined lest they slip away from Parliamentary control forever, Parliament responded with the Intolerable Acts, issued between March and June 1774. These acts were meant to punish the colonies, specifically Boston. They included the closure of Boston's port to commerce until the East India Company was fully compensated for the destroyed tea, the appointment of a military governor for Massachusetts, the replacement of the colony's elected council with an appointed one, and the provision that all royal officials accused of a crime could be tried in England or another colony rather than in Massachusetts. The acts also allowed military officers to requisition unused buildings to house their troops and granted more influence to the Province of Quebec, which further inflamed the Americans' anger. Watching the punishment Parliament was inflicting on Boston, the other colonies realized something had to be done; if Massachusetts lost its liberties, they all would.

In May and June 1774, as word of the Intolerable Acts first began to filter across the Atlantic, Boston wasted no time venting its outrage. At a town meeting, the residents voted against paying for the destroyed tea while the Boston Committee of Correspondence called on all Massachusetts merchants to boycott British imports and urged merchants from other colonies to do the same. To the south, the House of Burgesses announced that Virginia stood in solidarity with its Massachusetts cousin, going so far as to state that Boston was undergoing a "hostile invasion" (Middlekauff, 239). Other colonial assemblies and interest groups likewise condemned the Intolerable Acts.

AdvertisementConnecticut became the first colony to officially dispatch delegates to a meeting to discuss the terms of a potential boycott.

Many colonial merchants balked at the idea of entering into new nonimportation agreements, afraid that doing so would cost them business, as rivals would surely snatch up all available trade while they were busy boycotting. In late June 1774, Connecticut became the first colony to officially dispatch delegates to a meeting to discuss the terms of a potential boycott. The legislatures of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies followed suit, sending delegates to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The only colony not to do so was Georgia, which was threatened by a Creek Native American uprising on its frontier and did not want to risk losing British military protection by sending delegates to Philadelphia.

The 56 delegates of what would become known as the First Continental Congress convened in Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia on 5 September 1774. Among them were men who were soon to distinguish themselves as Founding Fathers of the United States: Massachusetts had sent Sam Adams and his cousin John Adams, as well as Thomas Cushing and Robert Treat Paine; from Virginia came George Washington, Patrick Henry, and Richard Henry Lee; New York's representatives included John Jay and James Duane. Other notable delegates included John Dickinson and Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, Silas Deane of Connecticut, Samuel Chase of Maryland, and John and Edward Rutledge of South Carolina. Even then, the sheer amount of talent and passion concentrated in Carpenter's Hall was apparent. John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail that "the magnanimity and public spirit which I see here make me blush for the sordid, venal herd which I have seen in my own Province" (Middlekauff, 248).

Once the Congress had gathered, its first order of business was to elect its president. For this position, the delegates chose Peyton Randolph, an eminent politician and scion of Virginia's most powerful family. Randolph would serve as the Congress' president until 22 October, when illness forced him to step down; he was replaced by South Carolina's Henry Middleton who presided over the final four days of the Congress. Charles Thompson of Philadelphia, though not a delegate himself, was appointed secretary of the Continental Congress, a position he would hold until 1789. After filling these positions, the delegates made the crucial decision that, going forward, each colony would be allotted only a single vote, no matter its size or population; this was deemed necessary to preserve the unity of the Congress.

AdvertisementOne of the Congress's first major acts was to approve the Suffolk Resolves. These resolves had been written by Dr. Joseph Warren, one of New England's leading Patriots, and had been adopted by Suffolk County, Massachusetts, on 9 September 1774. Described by historian Robert Middlekauff as "rhetorically extravagant even for a day rapidly becoming accustomed to the extravagant," the Suffolk Resolves condemned the "murderous" Intolerable Acts as wholly unconstitutional and called for the people of Massachusetts to band together in resistance (252). The Suffolk document urged citizens to disobey the Intolerable Acts and to refuse to pay taxes until the acts were repealed. It also insisted on a boycott of British imports and the raising of a Massachusetts militia to protect the colony's rights. The resolves were delivered to Carpenter's Hall on 17 September by Paul Revere, who acted as a messenger for the Congress, and they were immediately approved by the Congress as a gesture of solidarity towards Massachusetts.

Having demonstrated that the colonies stood behind Massachusetts, the Congress next turned to its primary task: hammering out the terms of a boycott of British imports. The delegates approved a so-called 'Continental Association', first proposed by Richard Henry Lee, in which a boycott of all imports from Britain, Ireland, and the British West Indies would begin on 1 December 1774, with the nonconsumption of British East India Company tea to commence immediately. Issues arose, however, once the Congress began to discuss when to prohibit exports to Britain. Delegates from South Carolina refused to agree to the Continental Association unless rice and indigo were excluded from the ban on exports, while the Virginian representatives wanted to hold off any nonexportation agreement until the tobacco harvested that year had been sold.

After weeks of negotiations, the Congress decided that nonexportation would only go into effect if the Intolerable Acts had not been repealed by 10 September 1775; the South Carolinians agreed to sign when the Congress agreed to exempt rice from the ban. Since the Continental Association was useless if it was not enforced, the Congress called for a committee to be set up in "every county, city, and town" (Middlekauff, 254). These committees were to inspect customshouse books and publish the names of offenders in local newspapers; those caught violating the boycott were to be branded "enemies of American liberty" (ibid). The boycott was effective, as imports from Britain dropped 97% in 1775 compared to the previous year.

When the delegates signed the Association on 20 October, the Congress' primary purpose had been fulfilled. But while they were gathered, the delegates decided to spend the next six days drafting a 'Petition to the King', in which they explained their grievances to King George III of Great Britain. At the time, George III was seen as misled rather than tyrannical, and several colonists held out hope that the king could still understand their plight. The delegates also wrote addresses to the people of Great Britain, the Thirteen Colonies, and Quebec, explaining their position. Finally, the Congress sent out letters of invitation to the colonies that had not sent delegates to Philadelphia, asking them to join the struggle: these colonies included Quebec, Nova Scotia, Saint John's Island, East Florida, West Florida, and Georgia. Of these, only Georgia would send delegates to the Second Continental Congress when it met in 1775.

As the Congress worked on its Continental Association and petitions, the need to define the rights and liberties of the American colonists inevitably arose. There was significant disagreement over whether the liberties of Americans were grounded in 'natural law', as popular Enlightenment philosophies might suggest, or merely in the British constitution. Joseph Galloway, one of the leading voices from the Congress' conservative wing, felt that basing American rights in the law of nature was a slippery slope that could lead to further defiance of Parliament and the ever-growing specter of armed conflict with Britain. Galloway told his fellow delegates:

I could never find the rights of Americans in the distinctions between taxes and legislation, nor in the distinction between laws for revenue and for the regulation of trade. I have looked for our rights in the laws of nature – but could not find them in a state of nature, but always in a state of political society (Middlekauff, 249).

In other words, Galloway saw the rights of Americans only within the framework of British and colonial law. The tie between Great Britain and her colonies, therefore, must be tightened, not loosened. Galloway attempted to offer a solution, introducing what he called a 'Plan of Union'. Under this plan, a colonial Parliament would be raised that would work in tandem with the British Parliament on issues related to the North American colonies; the colonial Parliament would have a royally appointed 'President General' and would consist of delegates elected by the colonial legislatures, who would serve three-year terms. Both colonial and British parliaments would have to approve any legislation before it became law, while local matters would be left to the colonial assemblies.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Galloway's plan was an appealing solution to those delegates who dreaded conflict with the mother country and only wanted to return to the status quo; John Jay and Edward Rutledge spoke in support of the plan. However, the more radical wing of the Congress did not see the merit of such a compromise. Reminding his colleagues that British politics were heavily informed by bribery and corruption, Patrick Henry warned that by creating a similar American institution, they would "liberate our constituents from a corrupt House of Commons, but throw them into the arms of an American Legislature that may be bribed by that nation which avows in the face of the world that bribery is a part of her system of government" (Middlekauff, 251). Galloway's plan was ultimately defeated in a vote of 6-5. The Congress then shelved the discussion of parliaments and rights and returned its focus to trade regulations.

On 26 October 1774, the First Continental Congress dissolved itself after sitting for nearly two months. With its approval of the Suffolk Resolves, it had shown its support for Massachusetts, and with the Continental Association, it had acted against the Intolerable Acts. It had affirmed its allegiance to the British Crown by sending a petition of grievances to the king while at the same time denying the authority of Parliament by refusing to send it a similar petition. Finally, the Congress had explained the colonial plight to the people of Great Britain, America, and Quebec and had asked Britain's other North American colonies to join its struggle. The Congress disbanded with the understanding that if the situation did not improve, it would reconvene in 1775.

Indeed, the situation would worsen in the months following the Congress' end. The militias raised by the Suffolk Resolves were put to use on 19 April 1775, when Massachusetts colonists and British regulars fought in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. When the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on 10 May 1775, it did not just have the Intolerable Acts to deal with but a rapidly escalating armed conflict. The Second Congress would act as the provisional American government during the American Revolutionary War; its major actions included the appointment of George Washington to the command of the Continental Army, the approval of the American Declaration of Independence, and the drafting of the Articles of Confederation. However, the success of the Second Congress certainly depended on that of the First, which demonstrated that the colonies could work together and unite in their defiance of Parliament.